Korean American artist Samantha Yun Wall explores cultural duality, memory, and societal stigma in her first major solo exhibition, which opened earlier this month at the Seattle Art Museum and runs through October 4.

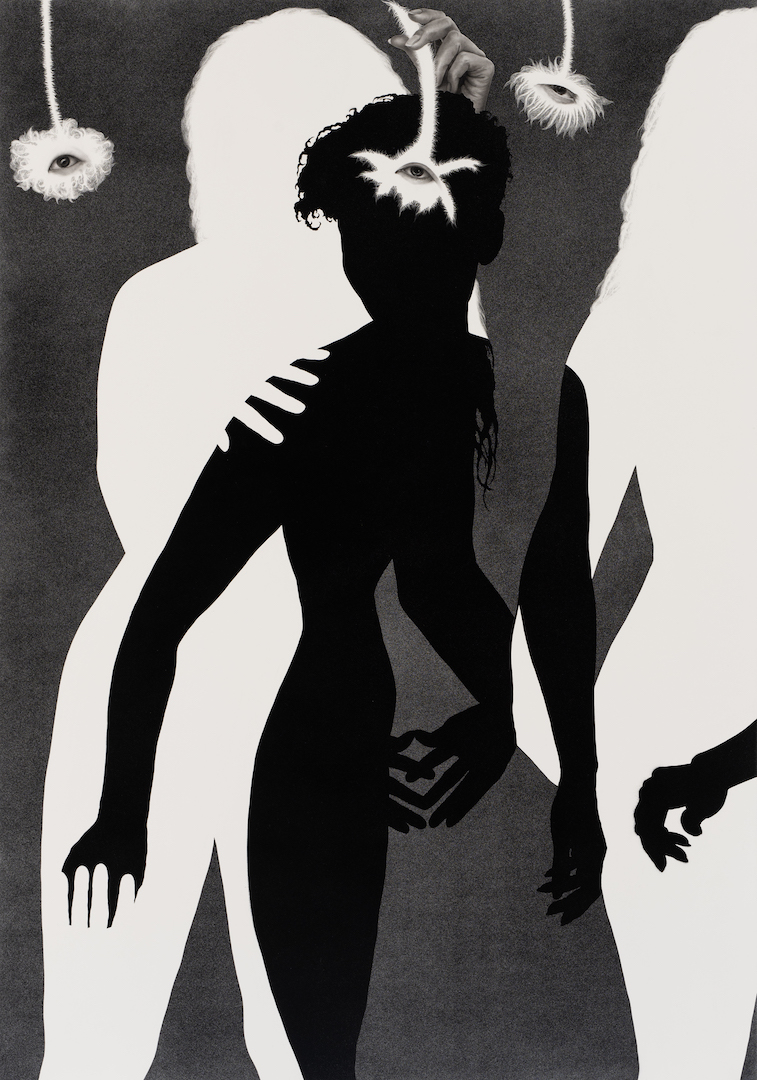

“What We Leave Behind” is a graphically arresting collection of 16 drawings and paintings. The works feature overlapping female silhouettes in stark black or ghostly white, but occasionally including shadings of charcoal gray. Most of these figures are featureless, but in some of the works there is special attention paid to the positioning or laying-on of hands. Other pieces depict silhouettes of the Pasque flower, already distinctive for its silky seed head and its fuzzy stems and leaves. But in Yun Wall’s representation, these flowers have an additional feature: there is a human eye drawn in the center of each flower.

What is this all about? The artist invites viewers to focus less on seeking answers, and more on asking questions.

What is this all about? The artist invites viewers to focus less on seeking answers, and more on asking questions.

To provide some context for the works in “What We Leave Behind,” Yun Wall took part in a recent Zoom interview from her studio in Portland, Oregon, to explain what led her down this particular track of investigation.

Born in Seoul in 1977, she doesn’t know her biological father, who was Black. Her mother, who is Korean, married a different American service member, and by the age of four, Yun Wall, her mom, and her stepdad left Korea when he was reassigned to a base in the United States.

But Yun Wall said she still has “a handful of memories” from her preschool days in Korea.

“Even though they are my oldest memories, they are still in the forefront of my mind,” she said. As a mixed-race child born into a homogeneous society, “my earliest memory of being ‘othered’ was there. I recall a teacher sitting me to the side, and feeling the gaze of everybody there. Not understanding the reasoning for my alienation… my questions of my place and the idea of belonging being so fragile.”

Upon arriving stateside, Yun Wall’s mom embarked with her daughter on a crash course in English. “My mother was teaching me at home, trying to help me assimilate. She stopped speaking Korean with me – that pencil in my hand came from her as part of my education.

“I don’t think she ever meant for me to draw… [but] drawing was a way for me to process the change in my environment… transition to who I needed to be here in the U.S.”

For the first several years, their family moved from base to base, and Yun Wall became accustomed to that way of living.

“It became a comfortable space,” she said. “I interacted with a lot of other young people my age who looked like me and who lived in this communal setting. It was this sheltered pocket of people from all over the country and the world and I didn’t appreciate how unusual our differences were – foods, rituals, different traditions.”

When she was 12, Yun Wall and her family relocated again – this time to a military base in South Carolina. And for the first time, she had to go off-base in order to attend school. This was when culture shock really set in.

“Everything I did was questioned,” Yun Wall recalled. “Every part of my identity was out of place. I was not Black enough, not Korean enough.”

She said she learned how to hold those disparate worlds simultaneously within herself, to become resilient enough to withstand the bullying.

Even so, Yun Wall said, “Those early experiences definitely were these inflection points that I’ve carried with me, and I feel them regularly still.”

About ten years ago, a death in the family made the artist realize that she didn’t have a strong connection to any traditions or rituals that would help her through her grieving process. She began to research her cultural roots for emotional support – and intuitively turned to Korean folklore.

The story that most appealed to her was a tale about the Pasque flower, which in Korea blooms through winter and into spring. That blossom’s characteristics, with the flower stem bent over and covered with white, fuzzy hairs – have earned it the nickname of the “granny flower” in Korea. The associated fable is of a grandmother neglected by her grandchildren until it is too late.

The story that most appealed to her was a tale about the Pasque flower, which in Korea blooms through winter and into spring. That blossom’s characteristics, with the flower stem bent over and covered with white, fuzzy hairs – have earned it the nickname of the “granny flower” in Korea. The associated fable is of a grandmother neglected by her grandchildren until it is too late.

The cautionary note of missed opportunity, along with the ritual mourning and spiritual reincarnation invoked in the tale, resonated deeply with Yun Wall. This myth has helped her reconnect with a culture and history that had long been absent from her life. That’s why Pasque flowers are showing up in her artwork now.

“It’s a way of talking about [my ancestors’] influences in ways that I don’t even understand… they’re people that I didn’t ever meet but I know they played a role in some way and it’s to honor them and acknowledge them but still deal with that ‘unknown,’” Yun Wall said.

And those eyes that occupy the center of Yun Wall’s Pasque flowers? Perhaps they bear silent witness to the ongoing struggle.

The art in “What We Leave Behind” asks us to consider what causes communities to fracture and forces them to disperse; the impact that such leave-taking has on individuals, families and entire cultures; the wisdom that is sacrificed in war or in diaspora; and the physical resources and empathy required to rebuild connections.

This provocative exhibit is hauntingly beautiful.

Barbara Lloyd McMichael is a freelance writer living in the Pacific Northwest.